Musk deers and musk deer products are in use for medical purpose in many countries across the Indian ocean. Stories about this animal were gathered and written by students. They are all part of a pedagogical project, funded by the National University of Singapore and the Université de Paris. The Bestiary site is a work-in-progress and a participatory educational tool, representing animals whose products or body parts are used to promote health and healing.

Wild Perfume

A Story by Isaac Tham Yijie

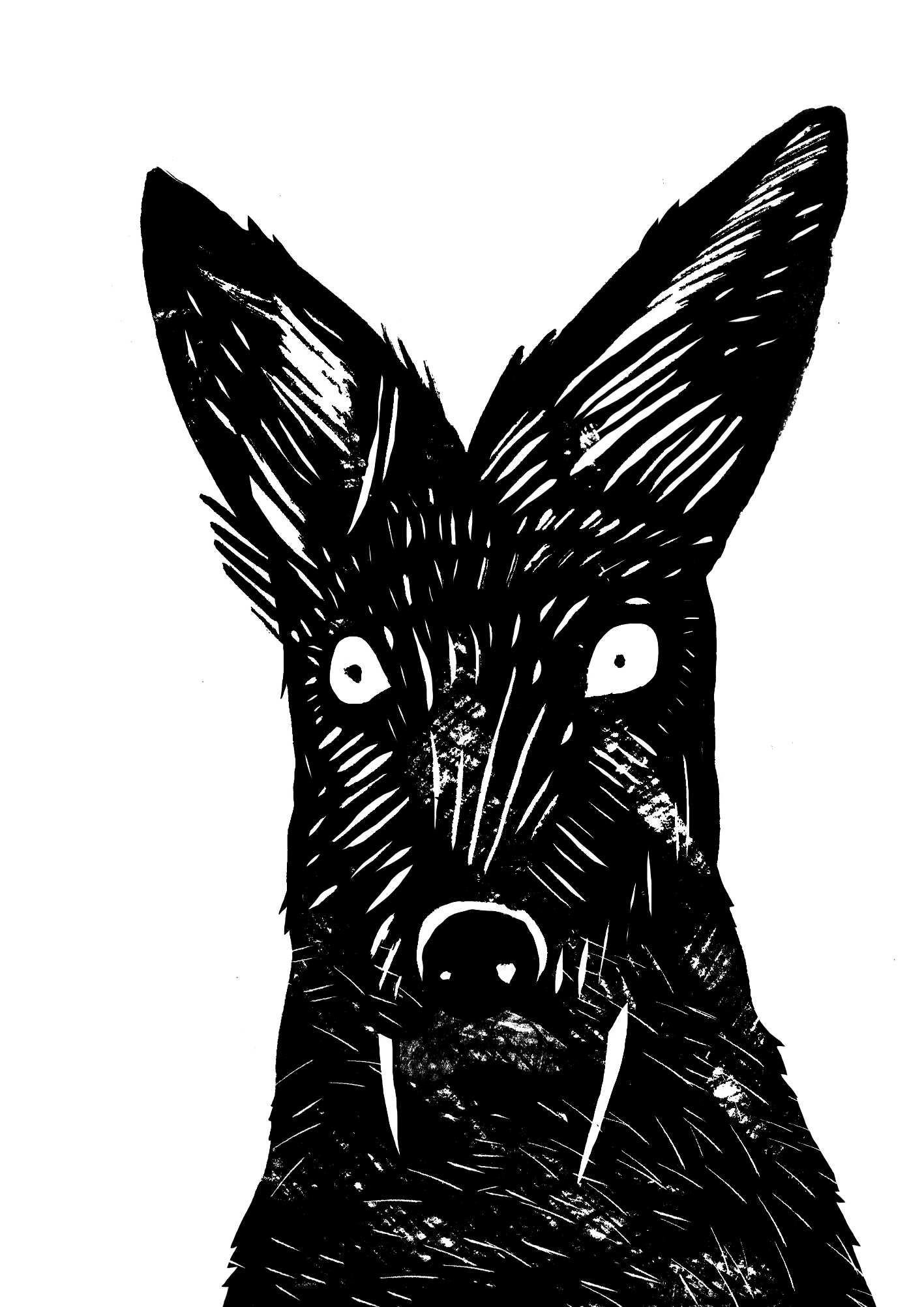

The musk deer (of the species moschus) is a small mammal native to South Asia, found particularly in the Himalayas. Despite being called musk deer, they differ from the deer (Cervidae family) by lacking antlers and having a musk gland, which is of economic importance to humans. Musk deer is exclusive to Asia, and does not live in other continents around the world. Their current endangered status hovers in the ‘threatened’ range, while the Siberian musk deer is ‘vulnerable’.

The earliest record of musk deer is from China in the later Han dynasty (25-230 AD). Found in ancient Chinese dictionaries, musk deer were described as “麝父”, literally meaning “father deer”, and remained present in subsequent dictionaries. While initially hunted for food, their meat was found to be difficult to digest, causing diarrhoea. Hunting for musk deer eventually stopped. However, they came to be utilized for their scent, used as perfume. Musk deer hide emits a scent enjoyed by the ancient Chinese, who used it to perfume clothes and rooms. The hide was mixed with Chinese ink used in paintings, to bring fragrance to the room. 麝香, a Chinese phrase meaning ‘scent’, literally means ‘musk’ being borrowed from the musk deer.

In addition to being valued for its perfume, musk deer are also treasured for their healing properties. According to legend, a hunter and his injured son stumbled upon a musk deer, whose scent was inhaled by the son, healing his wounds. Realising this property, the musk deer scent was stored by the hunter and his son, and brought home to heal the poor and sick. However, the scent was said to be dangerous for pregnant women. In the legend, an official stole the hunter’s bag which had the ‘magic’ scent and took it home, only for his pregnant concubine to miscarry upon inhaling the scent.

Due to the reputation of having a desirable scent with potential healing properties, the musk deer was highly sought after in ancient China. Their hide, at one point, was more valuable than gold, explaining its status as a treasure (not sacred), utilized for human needs. “Musk” comes from the Sanskrit word for testicle, and its usage is similar in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) too – as an aphrodisiac for men and as pain relief during menstruation for women. In ancient times, its musk could not be obtained without first killing the deer. Despite modern introduction of synthetic scents with similar effects, most practitioners of TCM continue to kill the deer. Due to the demand and value for their musk, deer populations have dwindled through time, and prohibitions in China have since been imposed to prevent further losses, with limited effectiveness.

Value in Asian Medicine

The musk deer has been an integral part of Chinese culture, particularly in the realm of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). It has also grown in prominence in Malaysia and Singapore, which import musk deer products from China. The musk from musk deer is used for a variety of purposes in Chinese medicine. It is a popular treatment for poor blood circulation and is believed to be beneficial to the nervous system. Also used as an aphrodisiac, musk is sold in the form of perfumes, sprays, plasters and powders.

Deer produce musk in the scent glands of the males, which is used in about 300 different TCM prescriptions. While this began around the fourth century, demand for TCM since then has grown throughout Asia and spread to some other parts of the globe. Consequently, trading and distribution of medicinal products such as musk have proliferated around the world. Captive deer generally produce far less musk than wild deer. Therefore, hunting for wild deer is common, even though captive deer are also used sometimes.

Traditionally, musk deer are not domesticated, and those that are captured are not kept as pets but ‘farmed’ for their musk. As wild deer produce more musk, and due to a severe lack of supply from musk deer farms, wild deer are hunted extensively in China to meet the growing demand for medicinal musk. Moreover, the musk deer are traditionally killed when obtaining the musk for TCM. This has resulted in illegal hunting and poaching of these deer, contributing to their endangered conservation status. The deer are not given reverence or sacred status, and are seen mainly as commodities for human use. As the Chinese folk tales became legends, musk deer became more commodified and were targets for human exploitation.

Disease Carriers

Unfortunately, musk deer are also carriers of zoonosis-related diseases. Pathogens such as Giardia duodenalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi are common bacteria in musk deer that can infect and cause diseases in humans. There are currently no medicines or vaccines available to treat such illnesses. One can, however, hope that the lack of vaccine or cure for these diseases might result in positive side effects provided humans become aware of the dangers of these diseases and refrain from (or reduce) the illegal hunting and killing of these animals.